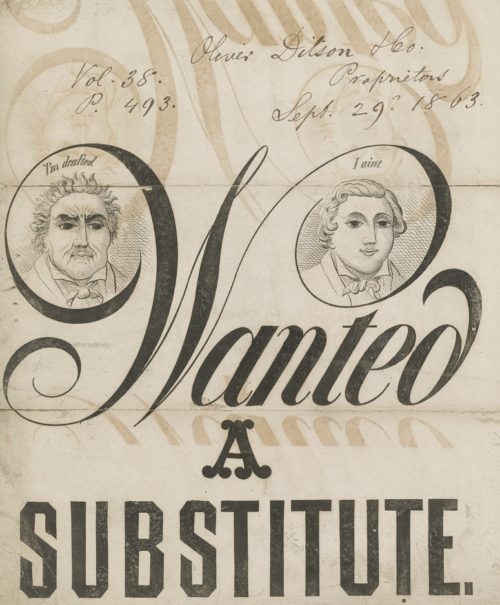

A new federal law, Enrollment Act of 1863 (also known as the Civil War Military Draft Act) was legislation passed on March 3rd of that year by the United States Congress to provide fresh manpower for the Union Army. Men were required to sign up to fight in the war against the states. But this new law had its issues and objectionable loopholes. Many cried out claiming that it was unconstitutional, and anger ensued over an exemption that favored the wealthy. One could pay a commutation fee of $300 (approximately $6,000 in today’s currency) or furnish a substitute who was more than likely paid, allowing an eligible male to be exempt from the draft. Clearly this was a privilege only available to the affluent. The length of the exemption was confusing as to how long it would last – the entire war or a limit of three years. To many, it was untenable no matter what it meant.

The drafting of men in New York City began during the weekend of Saturday, July 11th. On July 13th, just days after the draft had taken effect in New York City, what started as a small protest turned into a riot, later known as The New York City Draft Riots. But the protest progressed to a point that brought out the worst, most evil side of mankind. Early on Monday, July 13th, a small group amassed about 500 citizens to stand in front of the Provost Marshall’s office. Here the names of those ages 20-45 were called from the draft list to enter the war. Equipped with clubs, stones, brickbats, and what the newspapers termed ‘missiles,’ the men stormed the building and began to beat the draft officers and destroy draft books, papers, records, and lists. They then set the building on fire. All efforts to allay the riotous acts were met with the protesters’ increased anger. They began beating anyone who appeared to be ‘on the other side’ of the protest. The fire consumed the building, eventually consuming the entire block. Many of the officers and authorities were beaten close to death. Others were so bloodied, they were unrecognizable. This was just the beginning.

The mob, which included many children under the age of 12 (according to The New York Times), continued down to the Armory on Second Avenue between Twenty-first and Twenty-second streets where they burst through the doors using heavy sledges. Those protecting the Armory fired on the mob killing one and maiming several others. This incited the crowd further and they responded by setting the building on fire. The mob continued to look for buildings associated with the war which they would then destroy and plunder. This included the Fifth-Avenue Hotel where the Union League met regularly and Brooks Brothers’ clothing store which made Union soldiers’ uniforms. The anarchy increased with every hour. Nothing was exempt from plunder and destruction – including hotels, homes, and small businesses. When they came upon workshops, they would attempt to compel the owners and workers to join them, threatening death if they did not. The shops of those who failed to join were set on fire. Firemen were unable to put out any of the fires as the rioters had confiscated their equipment and shot the horses which had been drawing the firewagons. The buildings were lost to the flames.

The group then turned on the African American community. Thousands stormed towards the ‘Colored Orphan’s Asylum’ on Fifth Avenue. The home had originally been constructed by the Quakers with a main building that rose to four stories on grounds that encompassed the entire block between 43rd and 44th Streets. Over 200 children from infancy to 12 years old were residing there. They were quickly ushered out the back door as the rioters broke down the main entrance and began to steal and pillage. Breaking desks and furniture, the pieces were piled in the center of the building and lit on fire. Those who tried to stop the mob were knocked down or ignored. Within an hour and a half, the entire building was in flames.

This was only the first day. The riots continued until Friday, July 17th. The black community became a prime target of the mob who without provocation were randomly shot, beat, hung, mutilated, and lit on fire. In one instance, an infant was thrown from an upper story window of a home that had been broken into. The actual ‘cause’ of the protests had been lost early on, and there was no stopping the recklessness and insanity of the mob. They had no direction but destruction and death.

More details of the events following that first day and those who assisted in helping are documented in a book, The Draft Riots in New York: July, 1863 – The Metropolitan Police: Their Services During Riot Week. Their Honorable Record, written by David M. Barnes only months after the event. Several copies were printed, but a single copy was presented to the incoming mayor with his name embossed on the front cover. This rare find is now up for bid through Deb’s Finds. Interested parties should Contact Deb Silow at DebsFindsNJ@gmail.com for additional photos and pricing.